Introduction

Globalization has fundamentally transformed both national and international business practices, erasing barriers between countries and fostering cross-border interactions. This shift has prompted many companies, particularly from developed nations, to venture into developing countries, leading to a rise in multinational corporations (MNCs) operating globally.

Managing across cultures is a direct consequence of this trend. It involves expatriates moving to new cultural environments and managing teams with diverse backgrounds. This process can be highly challenging: while some expatriates adeptly navigate these complexities, others may struggle. Effective cross-cultural management requires adapting to a range of cultural norms while maintaining one’s own cultural identity. It demands a deep understanding of different cultures, management styles, and operational practices (Christian Dior Limited, n.d.).

Christian Dior Limited: An American Presence in Japan

Founded in 1946, Christian Dior Limited is an American company renowned for its diverse range of apparel accessories sold worldwide (Christian Dior Limited, n.d.). The company opened its first store in New York in 1949 and entered the Japanese market in 1997 (Christian Dior Limited, n.d.). With a global workforce exceeding fifty-five million, Christian Dior Limited exemplifies international business operations (Christian Dior Limited, n.d.). This paper will focus on cross-cultural management, particularly examining Christian Dior Limited’s operations in Japan, where the workforce predominantly consists of employees from the USA and Japan.

National Cultures

Cultural differences among nations are often more pronounced than their similarities. Culture can be defined as the shared value system of a society, which shapes both its physical and social environments and fosters cohesion and sustainability within the society (Hofstede, 2001). To understand different cultures, it is crucial to study the historical and traditional contexts of the respective societies.

The Japanese are known for their strong cultural pride, which they have preserved despite significant Western influence. Although Japan is largely secular, many of its values are rooted in religious traditions that emphasize harmonious relationships (Genzberger, 1994). Japanese culture is influenced by five main traditions: Shinto, Confucianism, Buddhism, Taoism, and traditional Chinese practices (Genzberger, 1994).

Shinto encourages harmonious relationships with others, while Confucianism provides a social code that emphasizes respect for authority and a paternalistic approach to leadership.

In addition, Japanese attitudes towards competing philosophies often contrast with the more exclusive viewpoints common in Western cultures (Genzberger, 1994).

Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions: Japan and America

Geert Hofstede is renowned for his analysis of culture as a dynamic interplay of competing forces that can disrupt societal practices rather than simply fostering cohesion (Hofstede, n.d.). His work underscores that managing across cultures involves navigating conflicting cultural norms. Extensive research has been conducted on national cultures and their impact on international business management.

In addition to Hofstede’s work, other significant studies include the GLOBE (Global Leadership and Organizational Behavior Effectiveness) Project and Trompenaars’ 7D cultural model (Aswathappa & Dash, 2007). These studies suggest that international managers who understand these cultural frameworks have a higher likelihood of succeeding in cross-cultural environments (Aswathappa & Dash, 2007).

The GLOBE Project identifies nine cultural dimensions that differentiate societies, including traits such as boldness, futurism, social devotion, sensitivity to gender, personality, achievement, and power (Aswathappa & Dash, 2007). These dimensions provide a comprehensive view of how societies differ in their values and practices.

Trompenaars, through research involving over 15,000 managers, identified seven dimensions of cultural differences. His model examines societies from both individual and collective perspectives, considering historical contexts, future trends, and societal aspects that extend beyond national boundaries.

Despite these contributions, Hofstede’s work remains the most influential. His five cultural dimensions revolutionized the field of international management:

1. Power Distance: This dimension measures the extent of inequality in power distribution within societies. In some cultures, power distance is pronounced, with significant gaps between leaders and followers, while in others, it is minimal (Hofstede, n.d.).

2. Individualism vs. Collectivism: Individualistic societies prioritize personal interests and self-reliance, whereas collectivistic cultures emphasize strong in-group connections and value group achievements (Hofstede, n.d.).

3. Masculinity vs. Femininity: This dimension explores how societies define and distribute gender roles. Masculine cultures focus on achievement and assertiveness, while feminine cultures value care and cooperation (Hofstede, n.d.).

4. Uncertainty Avoidance: This measures how societies handle uncertainty and ambiguity. High uncertainty avoidance cultures have stringent rules and a high need for predictability, whereas low uncertainty avoidance cultures are more accepting of ambiguity (Hofstede, n.d.).

5. Long-Term vs. Short-Term Orientation: This dimension, introduced later based on studies in China, differentiates between societies that focus on long-term planning and perseverance versus those with a short-term outlook (Hofstede, n.d.).

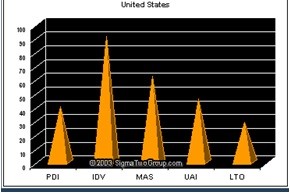

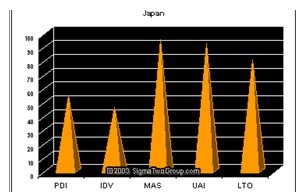

Hofstede dimensions for Japan and America

Managing in Japan

In contrast to the United States, Japan scores high across nearly all of Hofstede’s cultural dimensions. This highlights several key aspects of Japanese management and societal values:

- Acceptance of Inequality: Japan tends to view social inequality as a normal aspect of life.

- Dependence on Leaders: There is a strong emphasis on reliance on authority figures.

- Conflict Avoidance: Avoiding conflicts is highly valued in Japanese culture.

- Adherence to Laws: Legal frameworks are regarded as essential and should be strictly followed.

- Consensus Building: Achieving consensus is preferred in decision-making processes.

In addition, Japanese culture places a high importance on group decision-making, collective achievement, and shared responsibilities. Emotional expression is generally accepted, and organizations emphasize compromise and harmony. Managers in Japan often exhibit a fatalistic approach, accepting outcomes with an attitude of adjustment and flexibility (Aswathappa & Dash, 2007).

Managing Across Cultures

Richard Lewis, in his book ‘When Cultures Collide’: Managing Successfully Across Cultures’, classifies cultures into three main categories: task-oriented, highly organized planners, and people-oriented (Lewis, 2000). This framework aids in understanding how diverse cultures approach business and management.

David Ahlstrom and Garry D. Bruton emphasize that understanding culture is crucial for navigating the global business landscape (Ahlstrom & Bruton, 2009). They argue that culture comprises acquired knowledge that people use to interpret events and situations. This knowledge shapes their principles, thoughts, and behaviors, which are reflected in broader societal interactions (Ahlstrom & Bruton, 2009).

In practice, managing within a culturally diverse environment is challenging. However, the key to effective management lies in fostering a degree of uniformity while respecting cultural differences (Schneider & Barsoux, 2003).

Challenges in Cross-Cultural Management

Cross-cultural management often encounters various issues stemming from differences in value systems. These problems arise because cultures differ significantly, and these differences are deeply embedded in cultural practices, which are translated into actions. Consequently, individuals from diverse cultural backgrounds approach similar problems in varied ways, influenced by their distinct value systems (Bhattacharyya, 2010).

Another significant challenge is the impact of preconceptions and stereotypes. Stereotyping simplifies and categorizes individuals based on assumptions derived from observed characteristics. In cross-cultural teams, this often leads to negative stereotyping of others’ qualities and abilities. Such stereotypes can create self-fulfilling prophecies, where individuals communicate in ways that reinforce the traits others expect them to exhibit (Branine, 2010; Bhattacharyya, 2010).

Decision-making and problem-solving strategies also vary widely across cultures, creating operational challenges within organizations. Differences in educational backgrounds, work experiences, and cultural values lead to diverse approaches to problem-solving. For example, some team members might make decisions independently, while others prefer a participative approach. Some might rely on rational decision-making, gathering extensive information before deciding, whereas others may favor quick solutions (Bhattacharyya, 2010).

Communication issues further complicate cross-cultural management. Problems often arise from inadequate or poor-quality communication, including language barriers and non-verbal behavior. While English is widely used, some individuals may struggle with it and prefer to use their native languages. Additionally, non-verbal cues such as gestures and body language vary significantly across cultures, leading to potential misunderstandings (Bhattacharyya, 2010).

Technology adoption also differs among cultures. In modern settings, meetings increasingly rely on technological tools like telephones, video conferencing, emails, and online chats. However, cultural variations in technology use can impact communication and collaboration (Bhattacharyya, 2010). Furthermore, perceptions of time can differ; some cultures adopt a monochronic approach, focusing on one task at a time, while others use a polychronic approach, managing multiple tasks simultaneously (Warner & Joynt, 2002).

Strategies for Effective Cross-Cultural Management

Adler suggests that successful cross-cultural teams embrace and manage their diversity rather than disregarding it (Hamilton, 2007). To effectively navigate and leverage this diversity, Adler recommends the following strategies:

- Acknowledge Cultural Differences: Recognize and respect the diverse cultural backgrounds of team members.

- Select Members Based on Ability: Choose team members for their task-related skills, ensuring they are homogenous in capabilities but diverse in attitudes.

- Establish a Common Goal: Promote a shared purpose or overarching objective that transcends individual differences.

- Prevent Cultural Dominance: Avoid letting any single culture overshadow others.

- Promote Respect: Implement initiatives that foster mutual respect among team members.

- Encourage Feedback: Seek and act on high levels of feedback to improve team dynamics (Hamilton, 2007).

London and Sessa (1999) emphasize that successful cross-cultural managers must:

- Facilitate Diverse Work Environments: Effectively manage and motivate teams in diverse settings.

- Cultivate a Shared Culture: Create a sense of shared culture to unify team members.

- Foster Interdepartmental Relationships: Build productive relationships between different business units with varying cultural backgrounds.

- Select and Evaluate Staff: Skillfully choose and assess employees from diverse cultural backgrounds (London & Sessa, 1999).

Effective cross-cultural managers also adapt to local issues, ensure smooth transitions between tasks and jobs involving diverse teams, and balance extreme cultural differences through collaboration and negotiation (London & Sessa, 1999). Cultural sensitivity is crucial, as understanding and accommodating diverse cultural practices can foster cohesion within the organization (Wilson, Hoppe, & Sayles, 1996).

Adler (1997) highlights several key traits for successful cross-cultural managers:

- Cultural Sensitivity and Diplomacy: Demonstrate respect for all parties and communicate effectively.

- Problem-Solving Skills: Address cultural challenges synergistically.

- Negotiation Abilities: Possess strong negotiation skills (London & Sessa, 1999).

Merode (1997, cited in London & Sessa, 1999) adds that successful multicultural managers should:

- Motivate Teams: Inspire cross-cultural teams to achieve high performance.

- Conduct Effective Negotiations: Navigate cross-cultural negotiations adeptly.

- Recognize Cultural Influences: Understand how culture impacts business practices and staff evaluation.

- Manage Information Across Time Zones: Handle information across multiple time zones efficiently.

- Integrate Local and Global Insights: Use information from various sources for multisite decision-making.

- Stimulate Information Sharing: Foster a culture of information exchange within the organization (London & Sessa, 1999).

Steers, Sanchez-Runde, and Nardon (2010) recommend strategies for global managers in multicultural settings:

- Develop a Learning Strategy: Create a plan for continuous professional development as a multicultural manager.

- Understand Cultural Dynamics: Gain knowledge about different cultures and how to work effectively within them.

- Work Harmoniously with Diverse Managers: Build effective relationships with managers from other cultures.

- Enhance Cross-Cultural Communication Skills: Develop skills for communicating across cultures.

- Understand Leadership Processes: Learn how leadership processes differ across cultures and how to achieve synergistic outcomes.

- Motivate Employees Across Cultures: Understand how cultural differences affect motivation and performance.

- Build and Sustain Global Partnerships: Use negotiation skills to forge and maintain global partnerships (Steers, Sanchez-Runde, & Nardon, 2010).

Conclusion

Globalization will continue to shape the landscape of modern organizations, making cross-cultural management an integral part of international business. As managers from diverse cultural backgrounds assume roles in various regions, understanding and adapting to different cultural contexts becomes crucial. The influence of national cultures extends deeply into societal behaviors, affecting key institutions and shaping business and management practices. According to Hofstede, managing across cultures poses significant challenges, requiring international managers to study and comprehend the cultures they encounter. His five cultural dimensions provide a valuable framework for understanding these cultural differences.

When comparing the cultures of the United States and Japan, notable differences emerge that international managers must navigate. Hofstede’s dimensions reveal that Japan exhibits a higher power distance compared to the USA and has a more collectivistic culture in contrast to America’s individualism. Additionally, Japan shows a greater degree of masculinity and long-term orientation compared to the USA. Managing across cultures necessitates the development of cultural sensitivity, effective communication, conflict resolution skills, and strong negotiation abilities. It also requires leveraging the diverse talents within a team to achieve organizational goals.

International opportunities offer individuals the chance to cultivate cultural sensitivity and tolerance (Solomon & Schell, 2009). Ignoring cultural nuances can lead to failure, as managers may overlook critical aspects of the cultural landscape. American managers, for instance, face challenges integrating their individualistic tendencies with the collectivist nature of Japanese culture. To address these challenges, international organizations should create comprehensive cross-cultural management manuals to guide foreign managers. Additionally, managers must undergo training in cultural tolerance, cultural audits, and adaptation programs tailored to the foreign environment. Success in international settings hinges on implementing strategies that involve key stakeholders in both the formulation and execution of cross-cultural initiatives.

References

Ahlstrom, D., & Bruton, G. D. (2009). International Management: Strategy and Culture in the Emerging World. OH: Cengage Learning.

Aswathappa, K., & Dash, S. (2007). International Human Resource Management. New Delhi: Tata McGraw Hill.

Branine, M. (2010). Managing Across Cultures: Concepts, Policies, and Practices. NY: Sage Publishers.

Christian Dior Limited. (n.d.). Christian Dior. Retrieved from [Online source].

Genzberger, C. (1994). Japan Business: The Portable Encyclopedia for Doing Business with Japan. CA: World Trade Press.

Hamilton, C. (2007). Communicating for Results: A Guide for Business and the Professionals. OH: Cengage Learning.

Hofstede, G. (n.d.). Geert Hofstede Cultural Dimensions. Retrieved from [Online source].

Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions, and Organizations Across Nations. NY: SAGE.

Lewis, R. D. (2000). When Cultures Collide: Managing Successfully Across Cultures. UK: Nicholas Brealey Publishing.

London, M., & Sessa, V. L. (1999). Selecting International Executives: A Suggested Framework and Annotated Bibliography. Center for Creative Leadership.

Schneider, S., & Barsoux, J. (2003). Managing Across Cultures. NY: Prentice Hall/Financial Times.

Solomon, C. M., & Schell, M. S. (2009). Managing Across Cultures: The Seven Keys to Doing Business with a Global Mindset. New Delhi: McGraw-Hill Professional.

Steers, R. M., Sanchez-Runde, C. J., & Nardon, L. (2010). Management Across Cultures: Challenges and Strategies. UK: Cambridge University Press.

Warner, M., & Joynt, P. (2002). Managing Across Cultures: Issues and Perspectives. NY: Thomson Learning.

Wilson, M., Hoppe, M. H., & Sayles, L. R. (1996). Managing Across Cultures: A Learning Framework. NY: Center for Creative Leadership.